Typewriter

Periodcirca 1898

MediumSteel, nickel, leather, rubber, celluloid, oak, tin

Dimensions7.5 × 14 × 11.88 in. (19.1 × 35.6 × 30.2 cm)

With Lid Fastened On: 11.5 × 15.5 × 12.5 in. (29.2 × 39.4 × 31.8 cm)

With Lid Fastened On: 11.5 × 15.5 × 12.5 in. (29.2 × 39.4 × 31.8 cm)

SignedAcross the front of the typewriter in florid gilt script is the word "FRANKLIN." The company crest and motto is printed in gilt on the paten shield and reads "New Franklin / Perfection The Aim of Invention." Below the typewriter keys is a name plate "Franklin Typewriter Co. / No. 7 / Manufacturers, New York, U.S.A. / Patented Dec. 8th 1891 / Others pending." Serial number "9650" is stamped on the machine's frame at right, below the paten bar manual roller knob. On the enameled case lid is printed "FRANKLIN" in florid gold script.

ClassificationsOccupational Equipment

Credit LineGift of George H. Moss, Jr., 1994

Object number1994.12.1

DescriptionA typewriter constructed with a semicircular keyboard. The central molded face plate is padded along the inner edge with leather. Steel keys are arranged along the inside of the face plate in an upright striking position, resting against the leather pad. The ink ribbon is mounted in an upright reel position over the center of the roller bar. The typewriter frame is attached to a varnished oak base. The paten shield is ornamented with gilt scroll borders and the company's name "FRANKLIN." The letter keys at the front of the machine are of black celluloid with bold white characters, while the number and punctuation keys at either side of the semicircular keypad are of off-white celluloid with bold black characters. The return bar operates from the left hand side, mounted in an upright position and swinging to the right to advance the roller bar. A manual roller bar knob is mounted at right. The cover of the typewriter is of molded and soldered black painted tin with a wooden carrying handle.Curatorial RemarksThe gleaming black enameled steel and glossy varnished oak base of this Franklin typewriter represented, in part, a dramatic shift in both late 19th century society and economy. The first practical mass-produced typewriter was made by the Remington company in 1874. Its inventor, printer and journalist Christopher Lathan Sholes, believed that the typewriter offered women entering the work force the opportunity to "more easily earn a living." Post-Civil War American offices saw a dramatic increase in paperwork and the necessity to produce correspondence and documents quickly and accurately, something the new typewriting machines could offer. Women simply seemed able to operate these machines more easily than their male counterparts. An 1888 typewriter manual noted that typewriters were "especially adapted to feminine fingers...they seem to be made for typewriting." The promise of high wages as an office worker also exerted a strong pull on women seeking dependable employment. Although women's wages in the office were considerably lower than their male counterparts, it was much higher than many other options available to women. At the end of the 19th century in northeastern America, a female domestic servant earned between two and five dollars a week; a factory worker between $1.50 and $8.00. In comparison, a woman working as a typist and stenographer routinely made between six and fifteen dollars a week. In addition, an office setting was less physically demanding than a house servant, much less dangerous than in many factories, and was considered to be highly respectable employment. Business colleges saw the growing demand for skilled typists. In 1881, the New York City Young Women's Christian Association offered a six-month course for eight women. Less than a decade later, more than 1,300 private schools were offering typing and stenography courses for women seeking to enter the office work force. Although a number of newspaper and magazine articles appeared decrying the fact that women were "stealing" job opportunities from men, for the most part the idea of female office workers was quickly embraced. As one article noted, "women, by virtue of some of their most womanly traits, are capable of making the office a more pleasant, peaceful, and homelike place."NotesWellington Parker Kidder was born in 1853 in Norridgewock, Maine. At the age of fifteen he patented an improvement for steam engines and later studied mechanics in Boston. In 1889 Kidder applied for a patent for the Franklin, the first of several typewriting machines he would invent, which was awarded a patent in 1891. Kidder died in 1924. His obituary noted that Wellington Kidder was "considered the dean of the typewriter engineering world." The Tilton Manufacturing Company of Boston, Massachusetts, was the firm that actually produced the Franklin typewriter. The machine, with its distinctive curved keyboard, retailed for approximately $60 to $75. One of the machine's design drawbacks was that the operator could only see part of the letter or document being typed and had to lean over the high front shield to do so. Eventually the Tilton Manufacturing Company sold the rights to the Franklin machine, which was then produced by the Franklin Typewriter Company in New York beginning in 1892 until its bankruptcy in 1904.

Collections

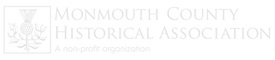

U.S. Office of War Information

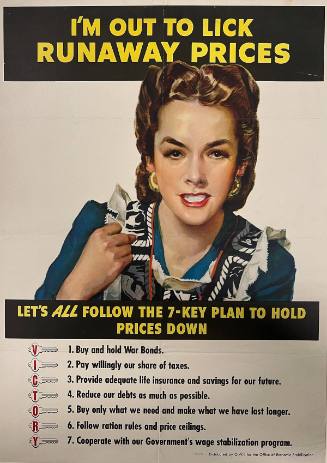

U.S. Office of War Information

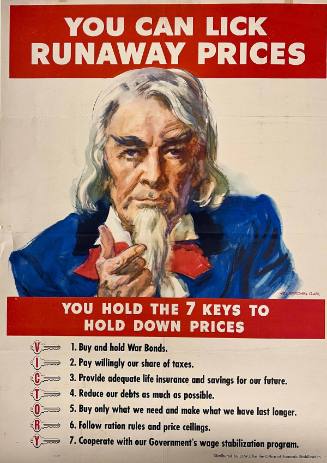

A. L. Holley

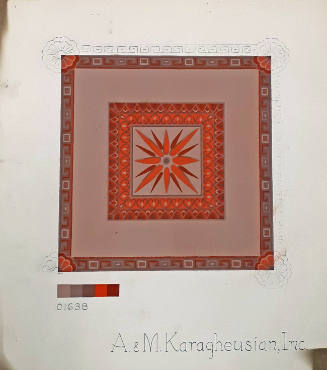

A. and M. Karagheusian

A. and M. Karagheusian